One of the benefits of Twitter for me is that I get great pointers for new things to read from the people I follow. One such came a couple of weeks ago from Simon Bostock. He drew my attention to “Bedford and the Normalization of Deviance” — an analysis by Ron Rapp of a recent National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) crash report. In Rapp’s words:

…after fifteen years in the flying business, the NTSB’s recently-released report on the 2014 Gulfstream IV crash in Bedford, Massachusetts is one of the most disturbing I’ve ever laid eyes on.

If you’re not familiar with the accident, it’s quite simple to explain: the highly experienced crew of a Gulfstream IV-SP attempted to takeoff with the gust lock (often referred to as a “control lock”) engaged. The aircraft exited the end of the runway and broke apart when it encountered a steep culvert. The ensuing fire killed all aboard.

…in this case, the NTSB report details a long series of actions and habitual behaviors which are so far beyond the pale that they defy the standard description of “pilot error”.

As we know from Atul Gawande’s work and elsewhere, pilots are supposed to work methodically from checklists. In larger aircraft, there will be more than one pilot so that each can check the other. In this incident, neither of those safeguards prevented a complete failure to attend to instrument warnings or follow instructions to avoid the crash.

Rapp suggests that the aggregation of errors in the face of clear instructions and warnings is an example of the normalisation of deviance. This is a term coined by an American sociologist, Diane Vaughan, in a study of the culture of NASA that contributed to the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. She summarised the concept in a later interview:

Social normalization of deviance means that people within the organization become so much accustomed to a deviant behaviour that they don’t consider as deviant, despite the fact that they far exceed their own rules for elementary safety. But it is a complex process with some kind of organizational acceptance. The people outside see the situation as deviant whereas the people inside get accustomed to it and do not. The more they do it, the more they get accustomed.

Vaughan’s work has been developed by others. I first came across the concept in a radio programme in 2010, in which Scott Snook was quoted:

Each uneventful day that passes reinforces a steadily growing false sense of confidence that everything is all right — that I, we, my group must be OK because the way we did things today resulted in no adverse consequences.

When I tracked down this quote to its source, in Chapter 6 of Snook’s book, Friendly Fire: The Accidental Shootdown of U.S. Black Hawks over Northern Iraq (an account of an incident in Iraq in 1994), I discovered that there was more useful detail, which is directly relevant to the growing use of checklists and processes in law firms and elsewhere.

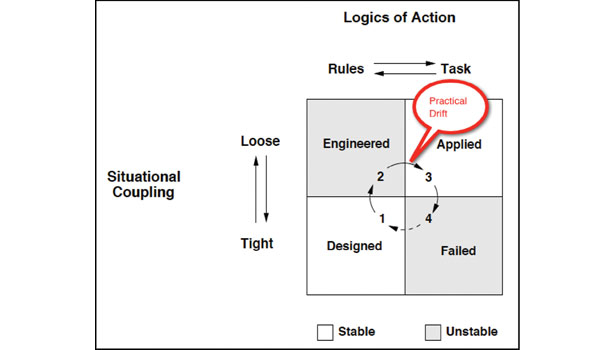

Practical drift between stability and instability

A useful summary of Snooks’s insight can be found in Industrial Safety and Hygiene News, by reference to the diagram linked below.

Snooks’s model describes behaviour in four quadrants bounded by the degree of ‘situational coupling’ and ‘logics of action.’

Situational coupling is described as loose or tight, depending on the extent to which parts of the organisation are free to operate autonomously. The more interdependence there is between different parts of the organisation, the tighter the situational coupling.

Logics of action are described as rule-based or task-based, depending on the primary driver of actions in a particular context. Rule-based actions are driven by checklists, policies, or other pre-determined norms. Task-based actions are more likely to be responsive to the immediate scenario or on local or personal habits — doing whatever is necessary to get the job done.

Snooks’s view is that two of these quadrants are mismatched and therefore unstable — that is, rule-based logics of action are unstable in loosely-coupled situations, and task-based logics are unstable in tightly-coupled situations. The ‘practical drift’ described by the circle of arrows in the centre of the diagram suggests how organisations move through the sequence from stable to unstable quadrants.

Law firm process and normalisation of deviance

How might this apply to the way law firms adopt (or improve) working processes?

The starting point would be a desire to define the nature and content of the policies or processes to be applied across the firm — these might cover working practices, compliance requirements or client-care standards, for example. These norms are set in the ‘design’ quadrant — where there is a common view that the firm needs to work together to achieve a particular goal (therefore tightly-coupled and naturally rule-based).

Once the rules are set, they become the basis for action, even when parts of the firm are working separately from other parts. This is the second quadrant, described as ‘engineered’ because actions are forced to be rule-based rather than driven by the context. Whilst the rules are new, they tend to be followed despite the mismatched nature of the situation. As such, the firm need have no cause for concern (apart from some teams reporting that the situation feels unnatural).

However, because of the mismatch, work in a loosely coupled situation will eventually default to task-based behaviours. This means that in the third quadrant (‘applied’ in the diagram), people will work in a way that feels more natural. They may ignore the wider organisational rules because they ‘don’t feel right’ or because a better outcome (personally or for clients) can be achieved by responding to more concrete or immediate needs.

This is where normalisation of deviance arises. All those involved know what the rules are, but they (tacitly or otherwise) agree to act according to a different set of standards. For the most part this is not a problem. As Snooks puts it, loosely coupled systems are both resilient and fragile. They can last a long time — until an external, possibly random, factor breaks them. This is where the original quotation resurfaces:

Each uneventful day that passes in a loosely coupled world reinforces a steadily growing false sense of confidence that everything is all right — that I, we, my group must be OK because the way we did things today resulted in no adverse consequences.

The emphasised phrase (omitted when I first heard the quotation) makes things much clearer.

Failure (the fourth quadrant) occurs when the system is pushed into a tightly coupled situation. This may happen when work that usually progresses autonomously is forced to take account of actions elsewhere within the firm or even externally. Where there is interdependence, task-based norms no longer work, because the newly introduced elements cannot be aware of the traditional behaviours (whether deviant or otherwise) of the loosely coupled team. In the worst-case (such as that described by Snooks in 1994 Iraq), previously loosely coupled teams have to assume that everyone else is following the rules, and behave accordingly, with fatal or disastrous effect.

Avoidance mechanisms

I think many, if not most, firms could identify situations falling into the failure quadrant. These errors may be minor, but they always have a cost — the persistence of a particular type of mistake-making inevitably suggests deeper problems to clients or insurers. How can they be avoided?

The standard response to persistent errors is to provide additional training and to highlight the importance of the rule-based systems even for loosely coupled situations. As I have pointed out before, this approach is rarely successful. On further reflection, I think a better response needs to be developed with the errant team.

Snooks’s description of practical drift suggests that the problem isn’t simply disobedience to organisational rules — it is that a rules-based logic does not match the needs of a loosely coupled situation. I suspect persistent errors in law firms occur more often in teams that work autonomously, and which are therefore more comfortable using task-based logic to structure their work. As such, then the answer must lie in one of two options.

The first is probably most attractive to firms with an interest in controlling the work people do. This would be to force interdependence between teams across the organisation. If the organisation becomes tightly coupled by default, adherence to common rules would be more natural. There may be additional benefits in such a refocusing of work, and they could make it more palatable, but otherwise it may be a struggle within the normal partnership model.

The second option is to open up a discussion about the way loosely coupled teams work, especially in difficult situations. This might include making work more visible, or clarifying the shared task-based logic used by different teams, so that the wrong assumptions aren’t made. Discussions of this type are likely to be very sensitive (particularly if they are positioned as a response to error-making), and so they probably shouldn’t be undertaken by the firm’s management. Impartial external, but informed, facilitation would be more fruitful. (Of course, if your firm is interested, I can do that.)

Even if no action is needed, being aware of practical drift should help firms understand better why and where their process improvements might succeed (and, more importantly, what might make them fail).